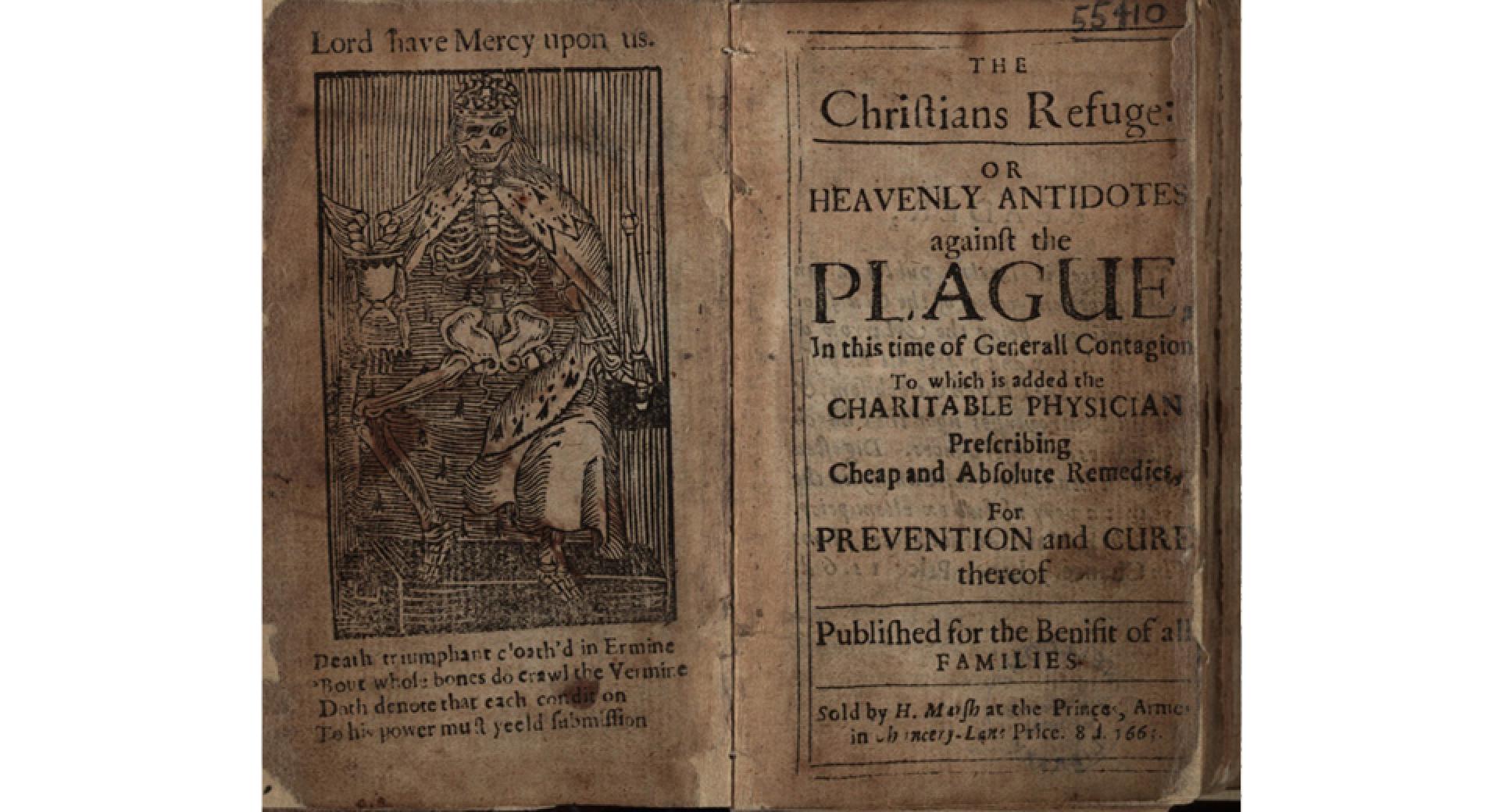

'Lord have mercy upon us.' Samuel Pepys and the Great Plague.

On this day in 1665, Samuel Pepys first noticed the effects of what was later to be known as the Great Plague. This is his diary entry;

'Thence, it being the hottest day that ever I felt in my life, and it is confessed so by all other people the hottest they ever knew in England in the beginning of June, we to the New Exchange, and there drunk whey, with much entreaty getting it for our money... much against my will, I did in Drury Lane see two or three houses marked with a red cross upon the doors, and “Lord have mercy upon us” writ there; which was a sad sight to me, being the first of the kind that, to my remembrance, I ever saw. It put me into an ill conception of myself and my smell, so that I was forced to buy some roll-tobacco to smell to and chaw, which took away the apprehension.'

June 7 1665

(Tobacco in those days was highly prized for its medicinal value, Pepys rarely used it, but the coffee houses of the day were full of smokers and chewers.)

We can read in these lines, the dread of the plague. The summer was to be long and hot, perfect conditions for its spread. Over 100,000 were to die of the disease before the year was out, up to a third of London's population.

The dread continues in a entry three days later on June 10.

'In the evening home to supper; and there, to my great trouble, hear that the plague is come into the City (though it hath these three or four weeks since its beginning been wholly out of the City); but where should it begin but in my good friend and neighbour’s, Dr. Burnett, in Fanchurch Street: which in both points troubles me mightily. To the office to finish my letters and then home to bed, being troubled at the sicknesse, and my head filled also with other business enough, and particularly how to put my things and estate in order, in case it should please God to call me away, which God dispose of to his glory.'

Pepys continues to chart the progress of the disease throughout the summer.

'...there dying this last week of the plague 112, from 43 the week before - whereof, one in Fanchurch-street and one in Broadstreete by the Treasurer's office.' (June 15, 1665)

'Thus we end this month, as I said, after the greatest glut of content that ever I had; only, under some difficulty because of the plague, which grows mightily upon us, the last week being about 1700 or 1800 of the plague.' (July 31, 1665)

'Thus this month ends, with great sadness upon the public through the greatness of the plague, everywhere through the Kingdom almost. Every day sadder and sadder news of its increase. In the City died this week 7496; and all of them, 6102 of the plague. But it is feared that the true number of the dead this week is near 10000 - partly from the poor that cannot be taken notice of through the greatness of the number, and partly from the Quakers and others that will not have any bell ring for them.

As to myself, I am very well; only, in fear of the plague, and as much of an Ague, by being forced to go early and late to Woolwich, and my family to lie there continually.' (August 31, 1665)

By late August, he had moved is wife, Elizabeth to Woolwich, hoping to keep her away from the contagion that was sweeping London. He stayed in the city throughout the summer, continuing to work at the Navy Office and attend meetings.

But like the good reporter that he is, Pepys continued to observe the plague, interspersing personal details with the numbers of the dead. 'It was dark before I could get home; and so land at church-yard stairs, where to my great trouble I met a dead Corps, of the plague, in the narrow ally, just bringing down a little pair of stairs - but I thank God I was not much disturbed at it. However, I shall beware of being late abroad again.' (August 16, 1665)

And the most descriptive passage of all. '...my finding that although the Bill [total of dead] in general is abated, yet the City within the walls is encreased and likely to continue so (and is close to our house there) - my meeting dead corps's of the plague, carried to be buried close to me at noonday through the City in Fanchurch-street - to see a person sick of the sores carried close by me by Grace-church in a hackney-coach - my finding the Angell tavern at the lower end of Tower-hill shut up; and more then that, the alehouse at the Tower-stairs; and more then that, that the person was then dying of the plague when I was last there, a little while ago at night, to write a short letter there, and I overheard the mistress of the house sadly saying to her husband somebody was very ill, but did not think it was of the plague - to hear that poor Payne my waterman hath buried a child and is dying himself - to hear that a labourer I sent but the other day to Dagenhams to know how they did there is dead of the plague and that one of my own watermen, that carried me daily, fell sick as soon as he had landed me on Friday morning last, when I had been all night upon the water ... is now dead of the plague - to hear ... that Mr Sidny Mountagu is sick of a desperate fever at my Lady Carteret's at Scott's hall - to hear that Mr. Lewes hath another daughter sick - and lastly, that both my servants, W Hewers and Tom Edwards, have lost their fathers, both in St. Sepulcher's parish, of the plague this week - doth put me into great apprehensions of melancholy, and with good reason.' (September 14, 1665)

The onset of winter seems to have lessened the numbers of the dead but Pepys was still recording that people were dying of the plague well into 1666. '.. at the Duke's with great joy I received the good news of the decrease of the plague this week to 70, and but 253 in all; which is the least Bill hath been known these twenty years in the City. Through the want of people in London is it, that must make it so low below the ordinary number for Bills.' (January 3. 1666)

Against this backdrop of pestilence, fear and apprehension, however, much of Pepys’s life in 1665 went on as usual. He still worked at the Navy Office, continued his adulterous liaisons, celebrated his cousin’s wedding, and pursued many of his interests. Surprisingly the year brought much opportunity and wealth Pepys’s way and, as the plague subsided, he wrote in his final diary entry for the year, ‘I have never lived so merrily (besides that I never got so much) as I have done this plague-time’.

Samuel Pepys was the great survivor.