'He was universally belov'd, hospitable, generous, learned in many things...'

On this day, May 26th, 313 years ago, Samuel Pepys died.

He had been ill for sometime, moving in 1701 to live with his friend and former clerk, Will Hewer, in what was then a small village outside London called Clapham. Here, he was cherished and nursed by another dear friend, his housekeeper, companion and perhaps mistress after his wife died, Mary Skinner.

After a painful struggle that lasted much of two days, he was given the last sacraments by yet another good friend, George Hickes, former Dean of Worcester, and died at exactly forty-seven minutes past three o’clock in the morning by his own gold watch. He was seventy years old.

He is perhaps remembered best for his diaries, written between 1660 and 1669. But Pepys was far more accomplished that simply being a diarist.

He was born the son of tailor in 1633, lived through the execution of Charles I, the rule of a dictator, Oliver Cromwell, the restoration of the murdered king’s son, Charles II, the deposition of that king’s brother, James II, by a Dutch invader, William of Orange and his wife (the deposed King’s daughter) Mary II, and the reign another daughter of James II, Queen Anne.

A startling contrast to the rather more sedate reign of our own Queen, Elizabeth II.

But despite spending at least three terms in prison for perceived threats against a variety of monarchs, Pepys achieved so much in his life.

He was a civil servant from 1656 until his forced retirement in 1689. During that time, he created the foundation for a Navy that, for the next 200 years, was to reign over much of the world. As Secretary of the Navy, he introduced a raft of new measures on the payment of sailors, the organisation of the fleet, the command structure and the building of new ships, that revolutionised it after the horrendous defeats in the Dutch Wars.

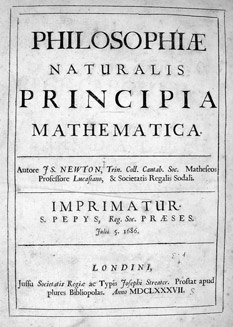

His other major achievement was as President of the Royal Society. It was during his presidency that a book was published, under the auspices of the society, that was to change man’s view of the world and nature for the next two hundred years - Newton’s Principia. It is no coincidence that Pepys’ name appears on the cover, he was actively involved in finding the money for it to be published.

The third major achievement was Pepys’ love of books. During his life, he amassed a library of more than 3,000 volumes. In his will, Pepys bequeathed the library to a relative, with the instruction that upon the death of the latter the collection should be transferred to Magdalene College — where Pepys had been a student as a youth — to be preserved ‘for the benefit of posterity’.

Pepys Library, Cambridge.

As his fellow diarist, John Evelyn, wrote in 1703. ‘May 26th. This day died Mr. Sam. Pepys, a very worthy, industrious and curious person, none in England exceeding him in knowledge of the navy…He was universally belov’d, hospitable, generous, learned in many things, skill’d in music, a very greate cherisher of learned men of whom he had the conversation.’

But, for me, there is one sentence in the diaries themselves that sums up Samuel Pepys' love and lust for life in all its joy. ‘The truth is, I do indulge myself a little the more pleasure, knowing that this is the proper age of my life to do it, and out of my observation that most men that do thrive in the world do forget to take pleasure during the time that they are getting their estate but reserve that till they have got one, and then it is too late for them to enjoy it with any pleasure.’ (March 10, 1666)

A wonderful philosophy for any life; eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we die.